CANSTRUCTION is an extraordinary annual design competition and the most unique food charity in the world. The competition challenges teams of architects, engineers, and contractors to build sculptures made entirely out of unopened cans of food. The large scale structures are placed on display and later donated to City Harvest for distribution to those in need. When the invite for the 25th annual CANSTRUCTION competition was sent to my firm, a group of us immediately jumped at the idea.

As designers, we anticipated that the hardest part of the competition would be the design of what we were going to build, we immediately set up weekly meetings and started brainstorming on what we need to build, an object that would leave a lasting impact on the people that came to see the exhibit. Little did we know, that the design was probably the easiest aspect of the puzzle.

When one of our colleagues, who had experience with CANSTRUCTION came in to listen to one of our meetings, she asked a simple question. HOW ARE YOU GOING TO BUILD THIS? Very naively, one of us responded “ With Cans! DUH!”. She then asked - “ ok, where are you going to these cans from? who is paying for it? and more importantly - once you get the cans, how do you suppose you’re actually going to construct this design of yours?” She reminded us that the rules of the competition were very strict, we could only use:

Velcro, magnets, zip-ties, tape, silicone

Rubber bands, nylon string, wire mesh or wire

Wood or steel rods, PVC pipe, threaded metal rods

Leveling materials (templates) not greater than 1/4″ thick (6mm)

Examples of approved leveling materials are: cardboard, foam-core, masonite, MDF, plywood, plexiglass, fiberglass

And like we had initially planned, we cannot use

Wood or metal beams, struts, steel tubes or bracing materials

Leveling materials (templates) greater than 1/4” thick (6mm)

Sheet metal, steel plates, Fiberock, or glass

Permanent adhesives or bonding process (soldering, etc)

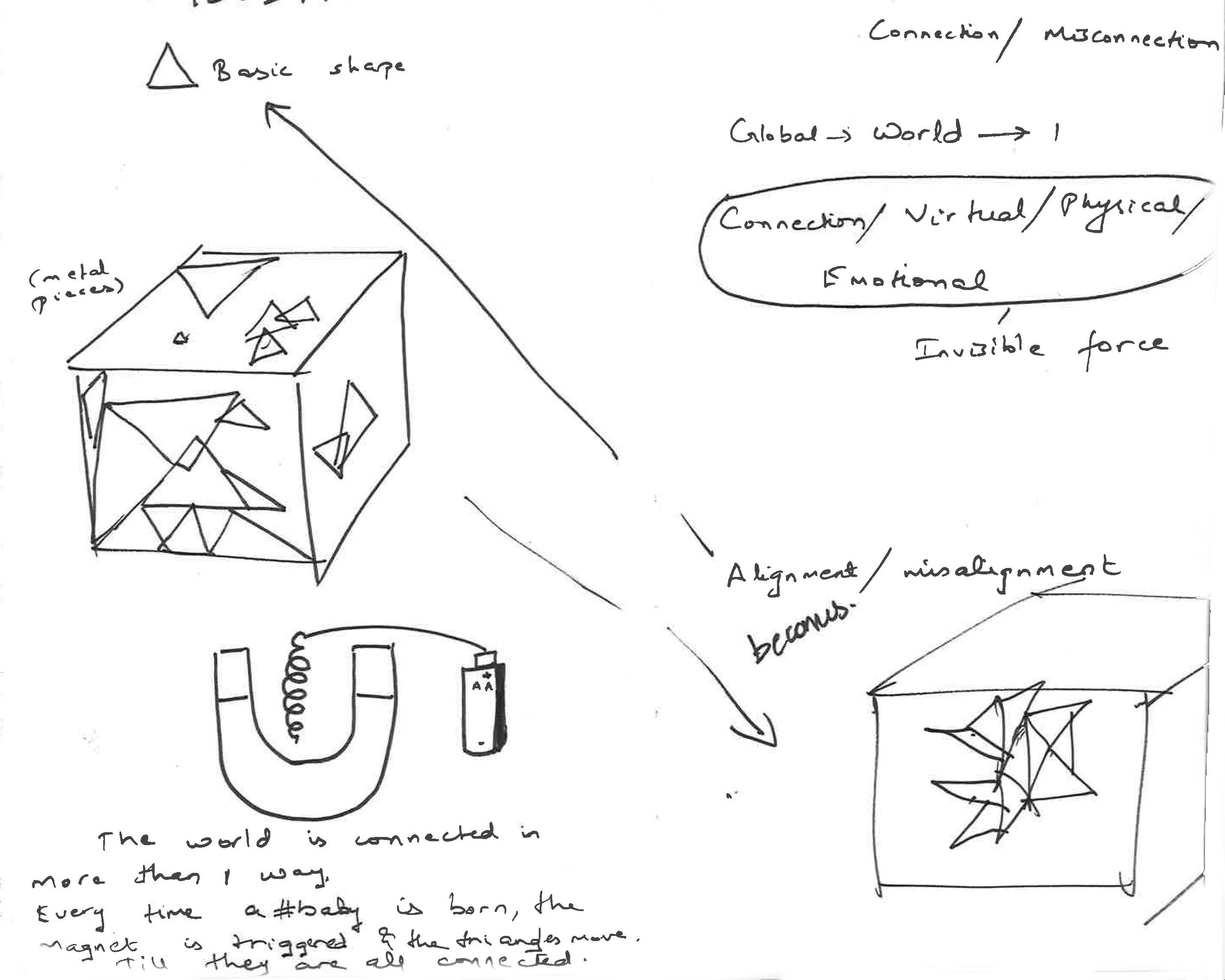

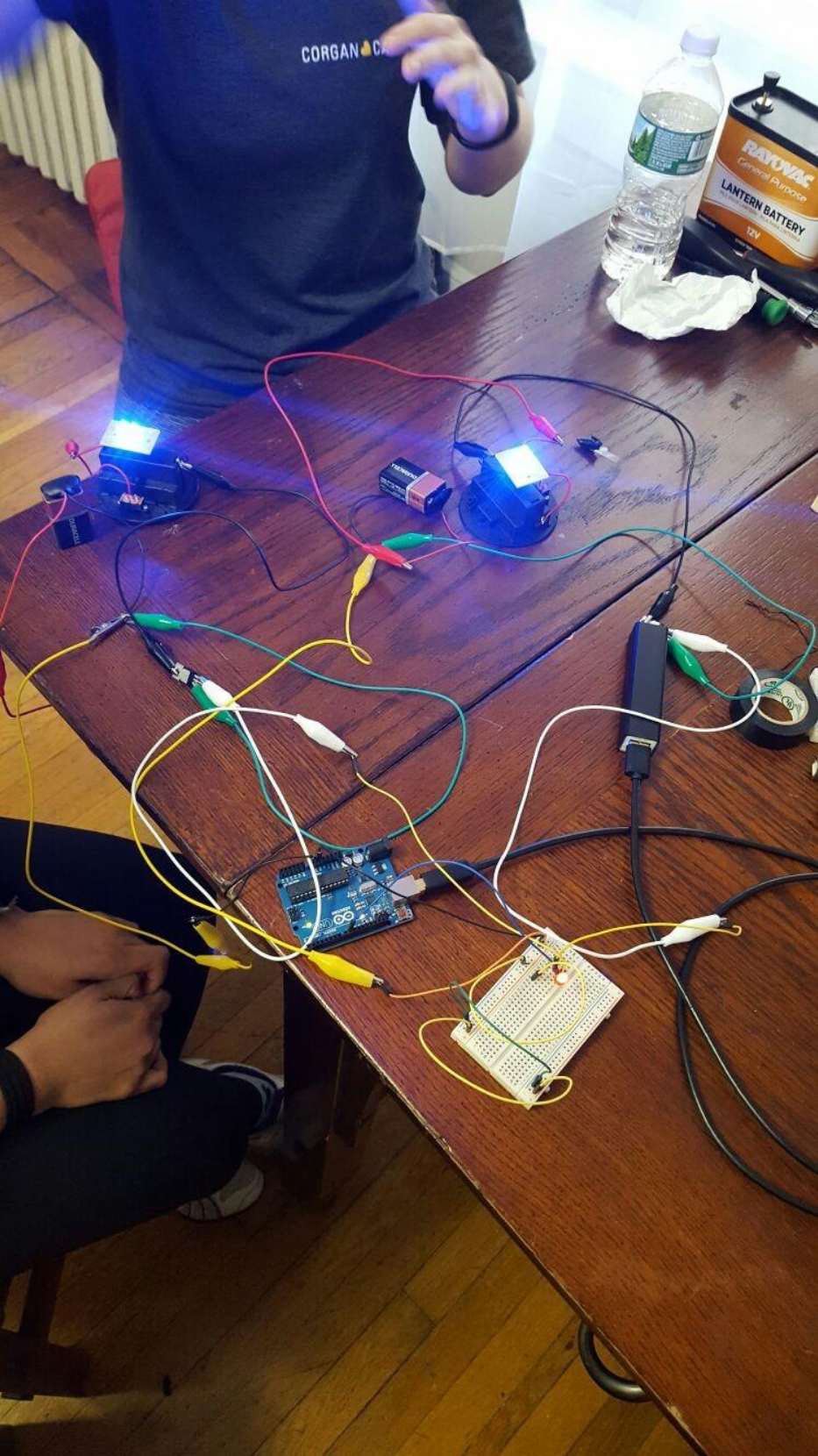

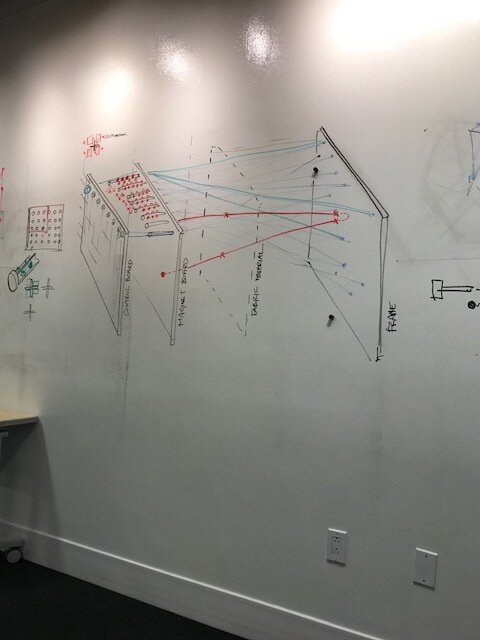

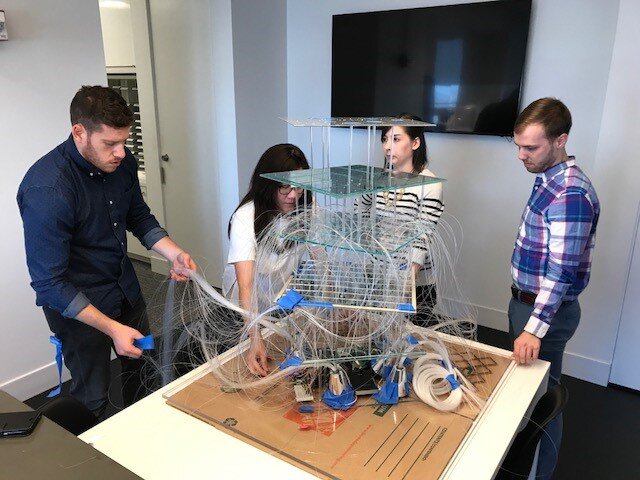

This changed our design process completely. We had to factor in how the exhibit would be constructed.

The next question was the size of the exhibit. We were allowed a maximum build area of 10’ x10’ x 10’. So we had to ensure that the exhibit fit within it. And we also had to ensure, that the exhibit was not an arbitrary no, but something that was in the denomination of can sizes.

The above considerations narrowed down our design options. We finally arrived at a concept inspired by Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory. Each one of us represents the minute hand to get us one step closer to a time when everyone would have access to healthy food.

My friend and colleague represented this interpretation beautifully in the mission statement below:

“You wish you find some time

To do something good for this world around you,

You ponder with you passive thoughts

Sitting at your desk

You wish you could turn back time,

To follow you passions,

To give and to love,

You don’t have to sit and wait,

The ground is caving beneath our feet.

For the time is now,

Together our minds are an infinite core of energy,

We CAN build the world piece by piece,

For the TIME is NOW

We CAN leave a continual imprint

And hope against hope,

That there is time,

When there is food and nourishment for everyone on this planet we call home. ”

As we worked towards recreating this concept image, we realized that the exhibit didn’t represent the idea of the “ melting clock” too well. And it definitely didn’t express the notion that time is running out. This changed the form of our exhibit. We took out a portion of the cube, cantilevered the clock from the cube to express the notion that time is running out.

The toughest part of this exhibit was the construction of the cantilever. But the weight of the cans, forming the clock and the weight of the cans forming the melted cube, were carefully balanced to allow the cantilever to be self supported.

We finally made it build night. Please click the link below to see the timelapse of our construction.

In conclusion, the event was a huge success and we learned so many things about design and construction in the process.

This however, would not have been possible without the contributions we received from our clients, sponsors, friends and family.